Learn from Japan’s Farm to-School Food Education: Four Steps to Cultivate Culinary Innovation and Sustainable Agriculture

Jenny Fan(China Productivity Center Agriculture Management Department)

Regardless of the strategy or local practical experience, Japan is a forerunner for all Asian food-importing countries concerning the development of food education. Since Japanese agricultural conditions and challenges in international trade and economy are similar to Taiwan, its success is worth emulating.

In recent years, Japan's domestic agricultural industry has been impacted by the globalization of trade and the regional economic integration. To maintain its domestic food security, agricultural industry development, and longevity of its citizens, Japan enacted the Basic Law on Food Education in 2005. Through the implementation of food education, Japan helps its citizens across age groups to develop healthy eating habits, promotes traditional dietary culture, and implements the local production for local consumption policy to increase consumer demand for domestically produced agricultural products.

Viewing the impact of regional economic integration, trade liberalization, rising global food prices, and increasing awareness of food safety on Taiwan’s agriculture industry, it is hoped that promotion of food and agricultural education will increase demand for domestic agricultural products, promote consumption of Taiwan good agricultural products, establish reasonable price for domestic produces, advocate domestic agricultural production, consolidate food safety, and bolster the agricultural development and transformation in Taiwan. Since Japan’s national strategy for food education and its nationwide basic plan on food education has been the beacon for Taiwan’s research on the food and agricultural education, we will use specific government agencies and elementary schools in Okayama Prefecture to illustrate the current state of food education in Japan.

Central Cross-functional Collaboration for Promotion

Japan’s food education was promoted by the Cabinet Office in the ten-year period from 2005 to 2015 and with cross-functional collaboration of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Food Safety Commission of Cabinet Office, and the Consumer Affairs Agency. Therefore, although the Japanese food education integrated unit was moved to the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in 2015, relevant ministries continue to promote food education through cross-functional collaboration based on a past cooperative basis. In addition, the central government of Japan has established a national-level Basic Law on Food Education and a food education promotion initiative updated every five years. Local government on the prefectural and municipal level also have local food education promotion initiatives.

The actual results of promotion are as follows: the effectiveness of execution, process, goals, and resources integrated agencies of local governments in promoting food education varies. Also, agricultural, health, and education agencies across the nation usually promote the food education for their main agenda individually; they only support and exchange information when necessary.

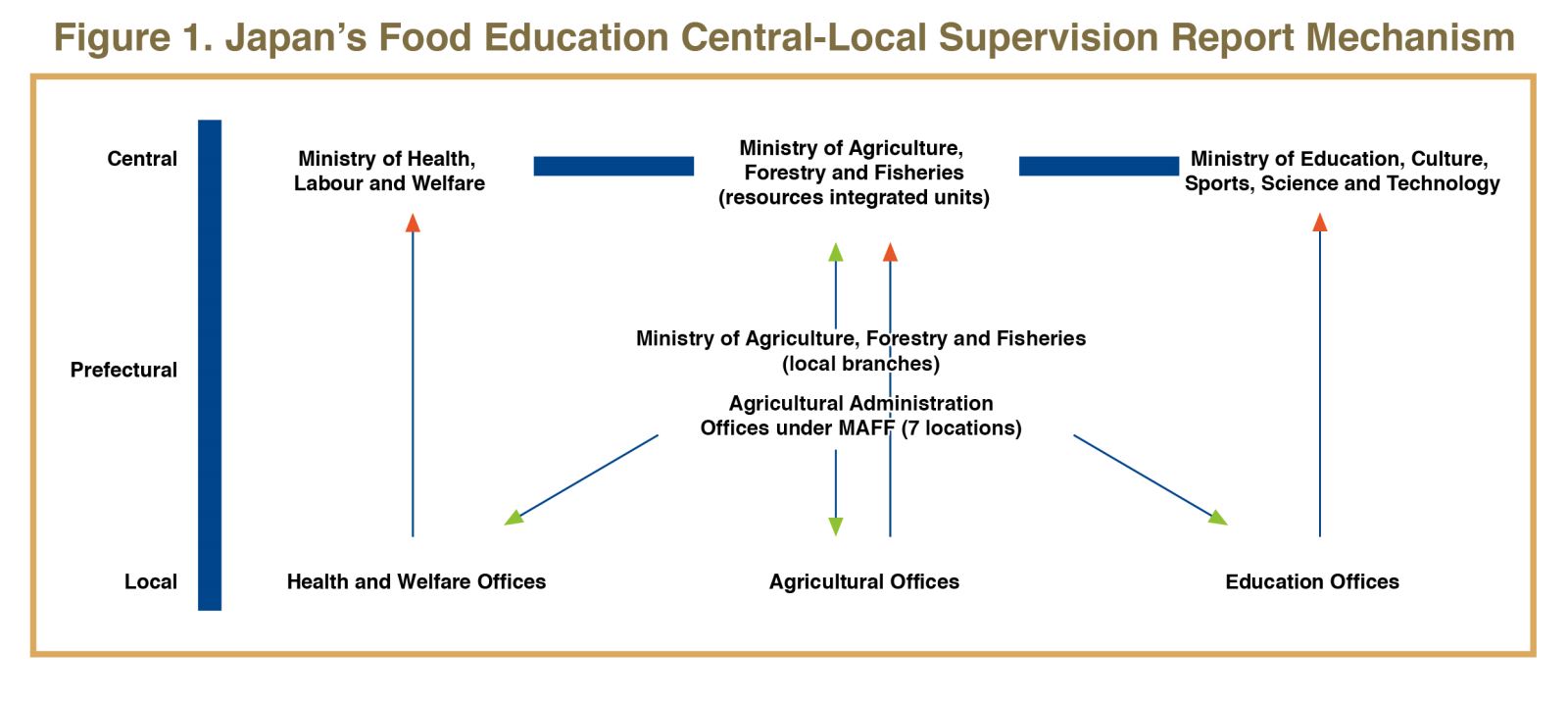

The local agricultural administration offices operate under the umbrella of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and supervise the local government units responsible for promoting food education. Furthermore, local government units in charge of health, agriculture, and education directly report the food education related affairs to its central authorities, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Japan’s Food Education Central-Local Supervision Report Mechanism

Efforts of Local Governments

The Okayama City Government does not have a unit dedicated to promoting food education. Instead, it is jointly implemented by the Health and Welfare Office of the Bureau of Social Welfare and Public Health, the Board of Education, and the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Office. These government organs all have their own food education promotion goals and agendas, and the Health and Welfare Office serves as a contact window for resources integration. According to the 2017 overseas observation tour report of the Council of Agriculture of the Executive Yuan, the main promotion projects of Okayama City include the use of domestic (or local) agricultural products for school lunches in charge by the education department as well as consumer awareness campaign of agricultural products produced in Okayama.

Regarding the "proportion of domestic (or local) agricultural products used in school lunches," the proportion of local produce in school lunches in Okayama City is 40%. Because of Okayama’s abundance in agricultural products, the percentage is higher than 30% set by the central government; however, the value is still lower than 50% set by the Okayama Prefectural Government. On the topic of "increasing public awareness of consuming agricultural products produced in Okayama City," the government conducts a survey once every two years by sending 10,000 questionnaires to the local residents to have an understanding of the consumer awareness of Okayama City’s agricultural products, and an average of 5,500 questionnaires are returned.

Promotion Efforts of the Public Association

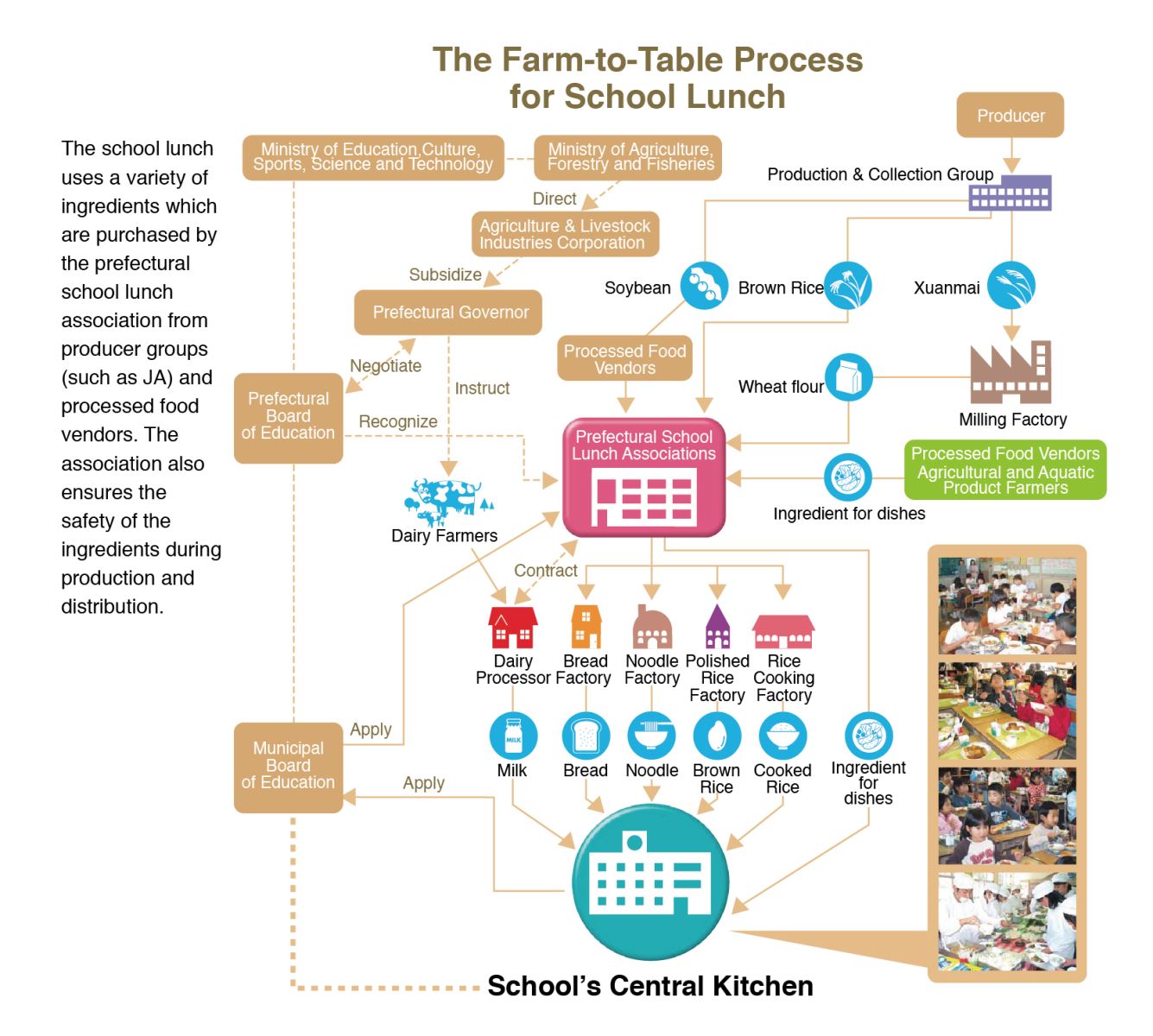

The main function of the Japanese "school lunch association" is to provide stable supply and sanitary management of school lunch ingredients in public schools. Currently, the lunch ingredients of most schools are still under the responsibility of prefecture-level school lunch associations. However, the administrative practices of school lunch associations are different depending on the region. For example, the School Lunch Association of Okayama Prefecture focuses on the management of the purchase and distribution of school lunch ingredients. Any opinions regarding school lunch are referred to the prefecture-level board of education (hereinafter referred to as the Board of Education) instead of the school lunch associations.

Taking Okayama Prefectural School Lunch Association as an example, the process of lunch ingredient distribution and sales in public schools (elementary, middle, and high schools) is roughly as follows: producer groups (such as Japan Agricultural Cooperatives, etc.) → purchase of food ingredients by school lunch associations in each prefecture→ processing of the ingredients into food by the food-processing plants sanctioned by the government → food prepared in the school's central kitchen for school lunch. In the past, the central government provided subsidies for school lunches to the Board of Education. Then, the responsibility of subsidy management was transferred to school lunch associations in different prefectures from the Board of Education. The school lunch associations and food processing factories also establish ingredient processing contracts.

The source of the main dish, milk, and other ingredients for lunch of the public schools in Okayama Prefecture is obtained through the above-mentioned joint procurement method by the prefecture’s school lunch association; vegetables and other ingredients are purchased separately. It can be seen that a public school’s lunch ingredients are partially managed by school lunch associations, and the remaining ingredients are purchased separately. Private schools are not part of the School Lunch Association network. Furthermore, municipal schools have municipal-level school lunch. Therefore, the distribution and sale of lunch ingredients in some municipal schools are co-managed by the school lunch associations of their prefectures, such as cities of Okayama and Kurashiki. The lunch ingredient source of the larger municipal schools in Okayama and Kurashiki is managed by their school lunch associations which are responsible for joint procurement of ingredients and tenders for producers and processed food vendors. Today, school lunch associations are structured as public interest incorporated foundations. There is no government subsidy, and they must bear their profits and losses. Thus, the actual function of school lunch associations is to jointly manage the school lunch ingredients and sell foods to the schools for lunch.

4 Steps of Benchmarking Learning

Since the beginning of food education in Taiwan, most activities take the form of improvement and awareness campaigns. Through the analysis of relevant domestic and foreign strategies and practices, we suggest referencing related domestic and foreign policies and procedures to maximize existing resources. Also, we advise to strengthen the site counseling and certification process of the food education and develop personnel training and teaching content, such as teaching materials, plans and modules. These policies will serve as a guide for the promotion of food education and lead to the establishment of an information platform based on the concept of “innovative regulatory sandbox.” Furthermore, we should continue to develop relevant resources and information on this platform to help dreamers and doers from various backgrounds and units in various fields to develop a well-rounded food and agricultural education.

The Farm-to-Table Process for School Lunch

Step 1: Site Counseling Mechanism

Comparing with Taiwan’s current relevant site certification criteria, it may be adjusted to the food and agricultural education site counseling mechanism which enables a link with the existing policies to achieve efficiency of the site management and verification and allows flexibility in using food and agricultural education sites. Therefore, we suggest to conduct comparatively analysis of leisure agriculture, environmental education, outdoor education, and Japanese education farms, thereby establishing the rules and conditions for planning the food and agricultural education sites.

Step 2: Personnel Skill Training

Based on the suggestions by relevant organizations, schools, and private groups for the food and agricultural education in Taiwan, it is widely believed that the promotion and teaching manpower empowerment or matchmaking and the teaching content referencing are most urgent for the current development of the food and agricultural education. For instance, the cooperative teaching by teachers, nutritionists, and agricultural professionals provides interdisciplinary professional guidance and translates professional knowledge such as agriculture, healthy diet and nutrition, and environmental ecology into popular science textbooks; these will help teachers and advocates deliver the correct knowledge and skills and allow consumers to practice these knowledge and skills in daily life. For example, the material can help consumers understand the origin and production of food, reducing excessive anxiety about food safety. The food and agricultural education should re-strengthen the links between people and land that have been alienated by economic and social development. Moreover, the food and agricultural education helps connection between agriculture and consumers through diet, dispels consumer concerns about food safety, and establishes social identity for agriculture.

At present, Taiwan's food sanitation-related technical staff requires to receive nutrition-related training programs, such as the food and culinary skills exams with a curriculum including healthy nutrition content, the on-the-job training program for childcare providers which includes application of the balanced and healthy diet knowledge to the infant nutrition and food preparation, the annual completion of eight-hour food sanitation lectures by the cook certificate holders as stipulated in the Regulations on Good Hygiene Practice for Food (including cuisine and nutrition education), and the certification of seed lecturer for food, agriculture and rice education. The future food and agricultural education personnel training program can be established based on the existing regulations to consolidate strength and avoid wasting resources on executing programs done prior.

Step 3: People-centric Textbook Compilation

Domestic scholar Chen Chien-Ting took the Japan’s food education for example and stated that to make basic information available to those who are interested in the food education, Japan provided a number of relevant teaching materials to the public before developing a food education plan. Currently, teaching materials for the food and agricultural education in Taiwan are relatively lacking, and most of them are inflexible and sometimes useless scientific knowledge. However, the purpose of the food and agricultural education is not to train professional agricultural operators or scientific personnel, but to create basic literacy in the public. Therefore, translating professional scientific knowledge into teaching materials acceptable to the public and developing an education module are important foundations for the development of food and agricultural education.

Step 4 Establishing and Evaluating Targets for Important Issues

By observing the development of food education in Japan and South Korea, we realized that the two countries regularly modify food and agriculture issues according to their economic and social structures and problems. They also convene meetings with experts and scholars for setting measurable targets to review the annual implementation results, which helps adjust policies for next year. As Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea are all food-importing countries in the Asian region, problems with agricultural production and market competition are also similar. Therefore, we recommend referencing the relevant research and systems of these two nations and establish target values that correspond to the key issues that address Taiwanese economic development and public lifestyle, thereby carrying out integrational management and reviewing the promotion effect of the food and agricultural education.

Case Study: Food Education Promotion of Nishiachi Elementary School, Okayama Prefecture, Japan

Nishiachi Elementary School located in Kurashiki City of Okayama Prefecture participated in the Super School Plan– “Super Food Education School Project-Deepening School-Family-Regional Cooperation and Learning Our Food and Health Together" organized by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan from 2014 to 2015. The plan promoted food education courses at every grade level. After the conclusion of the plan, the school continued to promote food education courses with the support of school staff and students’ parents.

The number of nutrition teachers in public schools below secondary education depends on the proportion of their teaching staff or the degree to which schools and parents view the importance of food education. However, the existing regulations do not require schools to have nutrition teachers. Take Nishiachi Elementary School for instance. The school's food education curriculum is mainly designed by two nutrition teachers and two health teachers and give lessons to students in food and health-related knowledge during school lunchtime with assistance from homeroom teachers. On the topic of a healthy and balanced diet, the teaching plans and materials are based on Japan's "Three Color Food Group" (i.e. starch and fat (yellow), calcium and protein (red), and fruit and vegetable fiber (green)) to guide students in understanding crops, required nutrients for the human body, as well as cooking and eating habits. The program also stresses on the coherence of all lessons and arranges curriculum and learning evaluation according to the physical and mental development of students in each grade. The following examples briefly describe the food education curriculum of each grade of Nishiachi Elementary School:

First Grade

Through lessons on the five senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch), the “Three Color Food Group,” and recommended cooking recipe, introduce the ingredients used for school lunch.

Second Grade

The five-month lifestyle class guides students to grow vegetables and observe the growth to understand the labor of agricultural production and the joy of harvest. Also, students share and discuss cooking methods with their families.

Third Grade

The food education on fish helps students understand the physiology of fish, nutritional value (fish oil and meat), the importance of food selection and a balanced diet.

Fourth Grade

Sociology class visits suburban farms and discuss farm stories and the processes of milk production, etc. The class also further discusses the environment of the farm, such as climate, terrain, rainfall, and nutritional content.

Fifth Grade

Family class guides students to discuss what they ate on a particular day, why they ate these foods, as well as the balance of the five nutrients and Three Color Food Group. Also, the class teaches students to design recipes and cook with rice and miso soup as menu staples.

Sixth Grade

Students learn about the nutritional balance of a meal and the basics of cooking in fifth grade. In sixth grade, they will learn more about cooking methods and the use of ingredients, with consideration on taste, seasonality, and cost of ingredients to strengthen good eating habits and disease prevention.